Intro: From the wake-up machine to the iconic Truckla, Simone Giertz has redefined the joy of creation through the art of “failure.”

Maker Faire Shenzhen 2025 is just around the corner, bringing together makers from all over the world. Through exhibitions, keynote speeches, hands-on workshops, and project tours, this grand event will showcase cutting-edge innovations and celebrate the spirit of invention.

This year, globally renowned Swedish maker Simone Giertz— formerly known as the “Queen of Shitty Robots”—joins Maker Faire Shenzhen 2025 as the Innovation Ambassador. This marks Giertz’s first appearance at Maker Faire Shenzhen and her long-awaited return to China.

The Making of the “Queen of Shitty Robots”

Simone Giertz is renowned for her wildly imaginative ideas and unique sense of humor. The robots she built were are often“not very functional,” yet they delivered unexpectedly hilarious moments.

Take her famous wake-up machine, for example — a robotic arm that literally slaps her in the face to get her out of bed. Or the “breakfast robot,” which was supposed to serve cereal and milk but instead creates complete chaos in the kitchen. Then there’s the lipstick robot, a mechanical arm that enthusiastically smears lipstick all over her face, turning a makeup tutorial into pure comedy gold.

Born in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1990, Giertz developed a passion for hands-on creation from a young age. In elementary school, she was the only girl in her class who chose woodworking over sewing. At age 13, driven by her fascination with plants, she cultivated over 90 varieties at home for observation.

Later, Giertz gained admission to the engineering physics program at KTH Royal Institute of Technology with outstanding grades. However, after just one year of study, she realized this was not her true passion and decided to withdraw from the program.

After leaving college, Giertz tried many different things — she worked as a web editor and journalist before going to vocational school to study advertising. Later, during an internship at an American engineering company, she was introduced to product design and manufacturing — an experience that would eventually shape her creative career.

The first project she built there was called “Retractable Guitar Strings.” It was a playful idea — guitar strings extended from a phone and attached to a belt, while the phone screen acted as the fretboard. Touching the strings triggered different sounds. It didn’t really make sense as a product, but it gave her an unforgettable thrill: the joy of turning an idea into something real.

She began focusing on the humor in her failed creations to ease the pressure and expectations she put on herself. In 2015, Giertz launched her YouTube channel uploaded a short video titled “The Toothbrush Machine.”

In the seven-second clip, Giertz wears a teal helmet fitted with a robotic arm holding a toothbrush. When she smiles, the arm swings into action, brushing her teeth for her. The video went viral, eventually racking up more than 750,000 views.

Shift Toward “Useful” Design

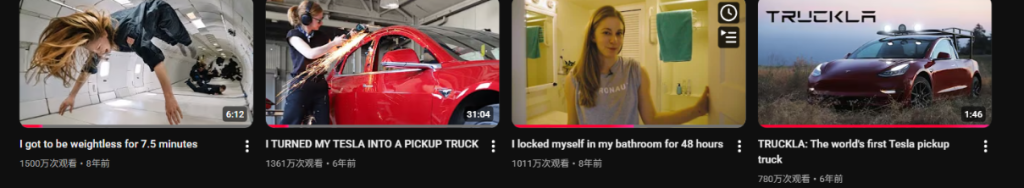

In 2017, two of Giertz’s videos simulating life in space each surpassed ten million views. One showed her spending 48 hours in confined spaces, like a bathroom, while the other offered a seven-and-a-half-minute glimpse of a zero-gravity experience

At the peak of her career, Giertz’s health began to decline. In 2018, she was diagnosed with a brain tumor and underwent surgery. Because the tumor was close to critical nerves, doctors couldn’t remove it completely. Eight months later, it recurred, and Giertz had to undergo further treatment.

Her illness led her to rethink the meaning of creation. She began to wonder if building flawed robots was, in some way, diminishing herself — making her feel small. Why couldn’t she become an expert?

At the same time, the drop in energy after surgery made it harder for Giertz to keep up with the “Shitty Robots” series. “I was always worried that eventually it would feel like beating a dead horse — the jokes would run out, and there’d be nowhere left to go.”

Truckla Project

In 2019, Giertz announced that she would stop making “Shitty Robot” videos, choosing instead to focus on projects that were genuinely useful. That same year, she challenged Elon Musk by spending a year converting a Tesla electric car into an electric pickup truck — the “Truckla.” The video has since amassed over 13 million views.

Following this, Giertz founded Yetch Studio, a company named after the pronunciation of her surname. Yetch creates playful yet functional designs, including an LED light check-in calendar, a “forever incomplete” white puzzle, screwdriver rings, and freely attachable hats. With a subtle “anti-conventional” spirit, these products continue her philosophy of blending humor with everyday life.

LED light check-in calendar

“I think it’s inevitable. Before, obviously, I wanted something that failed in the most unexpected or fun way possible. And now, when I’m developing products, it’s still a part of it. You make so many different versions of something, and each one fails because of something. But then, hopefully, what happens is that you get smaller and smaller failures. Product development feels like you’re going in circles, but you’re actually going in a spiral because the circles are taking you somewhere.” Giertz concluded.

Returning to China: From Student in Hefei to Speaker in Shenzhen

Simone Giertz has a special connection with China, where she is also known by her Chinese name, Jiang Xinmeng.

In 2006, at just 16, Giertz spent a year in Hefei as an exchange student and even appeared in a Chinese sitcom. She later described the experience as “one of the most surreal experiences of my life.”

After high school, she spent six months teaching English in Foshan. In 2016, shortly after gaining fame for her “Shitty Robot” videos, she visited Shenzhen’s Chaihuo Maker Space with a Swedish innovation group to meet and exchange ideas with local makers.

After nine years, Giertz returns to Chaihuo Maker Space to take part in Maker Faire Shenzhen for the first time. She will deliver a keynote speech on the morning of November 16, titled “The Creative Benefits of Lowering the Bar.”

This year also marks the 10th anniversary of her first “Shitty Robot.” Giertz’s journey has been far from linear—it has been an evolution from deconstruction to reconstruction. In a rapidly changing world, her ability to evolve, embrace iteration, and fearlessly start over may be the most valuable lesson she offers.

We are really looking forward to Giertz continuing to bring unique innovations to Maker Faire Shenzhen 2025. Meanwhile, we cordially welcome you to the Vanke Design Commune in Nanshan on November 15-16.

Finally, check out Simone Giertz’s amazing projects from the past year. Interested viewers can head over to her channel for more content! 👉 https://www.youtube.com/@simonegiertz

Visitor Register for MFSZ25

Over the past 12 years, the development trajectory of Maker Faire Shenzhen can be seen as a microcosm of the development of maker culture in China.

- 2012: “Gathering Small Wisdom, Journeying through the Great Future” – This was the first Mini Maker Faire in China, with less than 1000 attendees, and was more like a gathering within a small circle. But we saw the infinite possibilities emerging from the maker community.

- 2013: The slogan was absent, and the maker community was still small. – In the OCT Creative Park, there were cross-disciplinary exchanges among different creative communities, silently laying the foundation for cultural output.

- 2014: “Innovate with China” – the event was upgraded to the Featured level for the first time, with a significant increase in scale compared to previous years, and the beginning of professional independent forums. This year, makers began to enter the public’s view.

- 2015: “Everyone is a Maker, what are you waiting for?” – This year’s Shenzhen International Maker Week became one of the largest Maker Faires in the world. This year, the concept of “maker” was elevated to a national level, and the trend of “mass innovation, mass entrepreneurship” swept across the country.

- 2016: “My World, My Creation” – As the sub-venue of the National Innovation and Entrepreneurship Week, the event was held for the first time in the commercial center area, experiencing unpredictable weather from typhoons to scorching heat. Many makers succeeded in your entrepreneurial endeavors this year, but it seemed like there were even more failures. The hype around entrepreneurship shifted towards rationality.

- 2017: “Makers, Go Pro” – The event took place at the university campus for the first time, focusing on Maker Pros and providing a platform for diverse innovators and makers to showcase themselves, presenting more possibilities for the growth path of makers to the entire community.

- 2018: “Co-making in the City” – The main venue of Shenzhen International Maker Week, where individuals and groups with shared visions and values gathered to showcase stories, projects, and explorations of collaboration among different communities and people.

- 2019: ” To the Heart of Community, To the Cluster of Industry” – The event was upgraded to the Maker Faire Shenzhen, attempting to attract professional audiences and focusing on pragmatic aspects such as solving the needs of industrial upgrading and co-developin. It aims to build a platform for innovation and industry dialogue and collaboration.

- 2023: “Where Are The Makers?”– Starting from our own mission and values, we aim to explore the future direction of makers and the possibilities for commercialization. Though this question does not have a definitive answer, we do hope that through this event, we can communicate and share with every one of you, finding more ideas and directions together.

- 2024: “Everything is AI” – This year, we brought together over 120 exhibitors from around the world, attracting nearly 1,500 professional attendees from nearly 20 countries and over 20 provinces across China. The exhibition showcased a wide range of AI application projects and hosted 10 AI hardware-themed satellite events, alongside various workshops.